81: New remarks on Scanian language, Proto-Norse, Bronze Age symbolic language& Gutnish, 19/11/2025

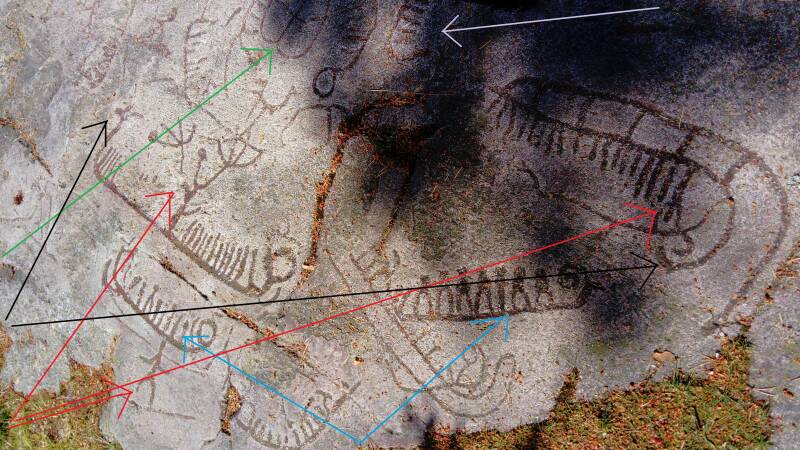

Written and published by Linden Alexander Pentecost. Published on the 19th of November 2025. This article like all my publications was published in the UK. Also like all of my other publications, no AI was used. This article is unrelated to any of my other publications, even though sometimes related topics are discussed. My previous publications on Scanian, some with their own Scanian tables, and other publications about Gutnish for example, are unrelated to the content of this article. My discussions in this article about Vikings, horned people, and Bronze Age Nordic art, are also unrelated to those discussed in other publications, including in for example article number 80 on this website, and for example my article more focused on clowns and Nephilim on this website, and other publications elsewhere. This article was published only on www.bookofdunbarra.co.uk. This article contains a total of 2777 words, making it a quite long article for this website. This article contains no sub sections but contains and discusses a lot of interesting topics, many of which are not made obvious from the title alone. The two photos included in this article were also taken by Linden Alexander Pentecost, me, the writer. One of the photos shows part of a Proto-Norse runic inscription, focusing upon a particular phrase, the second photo shows the detail of some rock art nearby to the Proto-Norse inscription, with arrows to point out and explain different parts of its symbolic language. The article also contains a table with Scanian, Scanian IPA, Swedish and English (unrelated to other tables I have made for Scanian).

Note that I originally intended to publish this article in front of you in "Silly Linguistics" as a part three of my "Languages of Southern Sweden" series, but I decided that this article would be better published on www.bookofdunbarra.co.uk, the website you are currently on. I will still publish another Silly Linguistics article about Scanian and other Southern Sweden languages, which will be separate from and have diffrent content to that in the article in front of you. I mentioned originally in my upcoming Silly Linguistics article pertaining to Kongsberg languages that the next Silly Linguistics article would be about Scanian - but this will likely not be the case now. Again, the article in front of you is being published instead.

I have previously had two articles published in Silly Linguistics on the languages of southern Sweden, in which I discussed Värmland Finnish, Värmlandic, Småländska and others. But the big boy language of Southern Sweden is one I have not yet discussed in Silly Linguistics but will here, namely - Scanian. (Which I have discussed elsewhere in detail, alongside other Southern Sweden languages not published in Silly Linguistics articles).

Nowadays, Scanian is often classed as a Swedish dialect in Swedish academia - conveniently. Scania was conquered by Sweden and so, classifying Scanian as Swedish seems to be, political. It is just another example of a standard language replacing and absorbing related indigenous languages. Considering that most of Sweden was not originally Swedish and became effectively conquered land, the same can be seen across Sweden, where ancient Nordic languages or dialect groups are conveniently called “Swedish dialects”, even though they were already separate from Swedish a long time ago.

In the case of Scanian, some also class it as a Danish dialect, because Scania was once part of Denmark. But notice how Scanian is always generally classified according to political boundaries, which often has little or nothing to do with actual indigenous culture and language.

It would be more accurate in my opinion to say that Scanian is neither Danish nor Swedish. It has similarities to both, in certain ways, but these similarities do not by any means, scientifically speaking, prove that Scanian is Danish or Swedish. Rather, it is its own language, with its own phonetic, grammatical and lexical components, which sometimes parallel to certain features of Danish, and sometimes parallel to certain features of Swedish.

Below is a short list of some Scanian features using more Swedish-based spelling:

1. Diphthongs. Scanian is known for its diphthongs, some of which are unique. Swedish a and å can be equivalent to Scanian au, ao or eu. Swedish i is often equivalent to Scanian ei. Swedish e can sometimes be equivalent to an ui in Scanian, and Swedish ä can also be equivalent to Scanian ai.

2. Scanian, like some Nordic languages in Denmark and elsewhere in Southern Sweden and elsewhere, has more voiced consonants. For example, Swedish titta på - “look at”, Scanian: tidda pao, Swedish att äta - “to eat”, Scanian: ad eda.

3. Scanian uses uvular-r sounds. For example skʁeiva – “to write”, Swedish: skriva, Scanian ʁeo – “peace”, Swedish: ro.

4. Commonly the words de and me, Swedish det and med, are pronounced with a different sounding diphthong than in Rikssvenska Swedish. The Scanian words maj, daj, saj are equivalent to Swedish mig, dig, sig, which are pronounced as though mej, dej, sej in Rikssvenska Swedish.

Dialect writers of Scanian use often a Swedish-based spelling, which will vary from speaker to speaker and dialect to dialect, as Scanian has a lot of inner variations, some of which correspond to surrounding areas like Blekinge and Småland. There is however a standardised Scanian spelling created by M. Lucazin. His spelling is a sort of inter-dialectal spelling that can be used to write most dialects of Scanian in a certain form, and the spelling is also in a sense etymological. I will include some examples of it here, with pronunciation in IPA, as his book UTKAST TILL ORTOGRAFI ÖVER SKÅNSKA SPRÅKET, MED MORFOLOGI OCH ORDLISTA 1◦ REVISIONEN is probably the best resource I have on Scanian phonology. All the Scanian forms in the table below, and their IPA equivalents are sourced from the aforementioned book. Note I have made other unrelated tables of Scanian words before, using the same orthography...

| Scanian (M. Lucazin’s orthography) | M. Lucazin’s orthography pronunciations of the Scanian words in this table | Rikssvenska Swedish form | Meaning in English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skáne | [skàʊ̯ːnɛ] | Skåne | Scania |

| fráğa | [fʁàʊ̯ːa] | fråga | ask |

| bád | [baʊ̯ːd] | båt – [boːt], Danish båd - [b̥ɔδˀ] | boat |

| mél | [mʊɪ̯l] | mjöl | flour |

| bækkahors | [bàɪ̯ka hʊɐ̯ːs] | ”bäckahäst”, näck | Something like a waterhorse or kelpie, or Swedish näck. |

| skéð | [skʊɪ̯ː] | sked - [ɧeːd] | spoon |

| swærð | [sʊ̯ɛɐ̯ː] | svärd | sword |

| bog | [beʊ̯ːg] | bok | book |

| væsnas | [ʋɛ̀ːznas] | väsnas | make a loud noise |

| swámp | [swaʊ̯ːmp] | svamp | mushroom |

| kørke | [ɕø̀ɐ̯ːkɛ] | kyrka | church |

| étt | [ʊɪ̯t] | ett | one |

| skriva | [skʁèɪ̯ːʋa] | skriva | to write |

| pág | [paʊ̯ːg] | pojke | a lad |

| givt | [ɪ̯eɪ̯ʋt] | gift | married |

| skow | [skeʊ̯ː] | skog | forest |

| sny | [snøʏ̯ː] | snö | snow |

| rése | [ʁʊ̀ɪ̯sɛ] | resa | a travel or a journey |

Note that there are many more localised pronunciations to the ones given above. In some areas for example, résa would be pronounced [ʁɔ̀ɪ̯sɛ], and in other areas [ʁàɪ̯sɛ]. Note that even when the Swedish and Scanian spellings look more similar, they are generally pronounced very differently. More examples with é and other diphthongs. I personally believe that Scanian is older than both Danish and Swedish in their standard forms. Note the way in which the Swedish and Danish words for “boat” are in many respects more similar to each other than either is to the Scanian form. If you would like to hear some Scanian, thencheck out the YouTube video, titled: På bred Skånska - Berit från Trelleborg ringer radion, uploaded by user: Skogssjön. The link to which is: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QYPN68mJqRQ&t=23s They have an interesting chat, including about the number ”6”, which in Scanian and in Swedish also sounds like the word for ”sex”.

But anyway, where does Scanian phonology even come from, and might it in some way paralell the phonology of another Nordic, or semi-Nordic language, written at least around 2,000 years ago? The language I speak of is not Old Norse, but what is termed Proto-Norse, although nobody knows what users of this language originally called it. It seems to have been the earliest form of Germanic written in the runic alphabet, specifically in a localised form of the Elder Futhark. It was pretty different from Old Norse (or rather, Old Icelandic, Old Swedish etc) in a lot of respects. Whilst it has been partially reconstructed, we don’t actually know if Old Icelandic, Swedish and Scanian for example actually “came” from Proto-Norse. In my opinion, Proto-Norse can instead be thought of as a kind of formulaic language, a transitional language between ”Norse” and the languages of their more ancient gods and ancestors, possibly not entirely Indo-European, but which had some kind of relationship to the Nordic languages. The important point I am trying to make is that it was in a sense formulaic, magical, and doesn’t necessarily represent how people actually spoke usually – but seems to represent a form of Indo-European formulaic language. There are examples in Scania, but the only example I have seen in person is in Blekinge, specifically the Björketorp Runestone. The inscriptions are transliterated as follows:

hAidz runo ronu fAlAhAk hAiderA ginArunAz ArAgeu hAerAmAlAusz utiAz welAdAude sAz þAt bArutz, and on the back of the runestone is also written: uþArAbA sbA. It is translated, approximately as: "I, master of the runes(?) conceal here runes of power. Incessantly (plagued by) maleficence, (doomed to) insidious death (is) he who breaks this (monument). I prophesy destruction / prophecy of destruction."

Photo below: the Björketorp Runestone, showing the shorter part of the runic inscription on the back of the stone, which says uþArAbA sbA, meaning ”I prophecy destruction/prophecy of destruction”. Photo taken by the author in the summer of 2017. The inscriptions are on two sides of this large monolith, with two other guardian monoliths or standing stones before it. This site is an example of the continuity between the Neolithic and Bronze Age megalith traditions and the Proto-Norse traditions. A similar thing can be observed in Ireland in Scotland with the use of the Ogham alphabet. Whilst some of the words and language in the Björketorp inscriptions are somewhat understandable, the actual meaning and purpose of the instription is not understood. Personally, I see the stones as being like guardian figures, and the general message is that never should they, like other megalithic monuments, ever be attacked, damaged or destroyed. In my opinion, the runic (Proto-Norse) language is the ”secret language” of these ancestral forces associated with the stones, under a newer Germanic interpretation.

There is so much to discuss about “Proto-Norse” runic inscriptions, but it is relevant that there are a fair number of these inscriptions around Scania and Blekinge in particular. The phonology of Proto-Norse in certain words often corresponds, interestingly, to Finnish cognate words, which is also interesting given the occasional mentions of “Finns” in Southern Sweden. For example runo – “rune, magical formulaic use of language” is cognate to Finnish runo – “type of sacred poem”. The Orkney Norn language, a now extinct Nordic language of the Orkney Islands in Scotland, also has a phonology that sometimes resembles Proto-Norse more than Old Norse, something which I have gone into detail about in other publications.

Whoever these speakers of “Proto-Norse” were, I think it likely that they did not simply appear out of no-where. Whilst “longships” are generally associated with the Vikings, it is important to note that there is evidence of this “longship” culture going back thousands of years earlier. Nordic or pre-Nordic people in the Bronze Age built megalithic monuments in the shapes of ships, back around 3,000 years ago, and this tradition survived in royal Scandinavian tradition into medieval times. Imagine a stone circle, essentially, but shaped like a ship. These monuments are not found everywhere in the Nordic world, and I am of the belief that this culture was not generally Norse, but rather existed as a specific culture within Norse and pre-Norse culture. There are a great number of these stone ships on the island of Gotland (which I will discuss later in this article), but also there are many examples in Scania, Bohuslän, Denmark, and also some in Northern Germany and in the Baltic Countries. This, to me at least, suggests a cultural background which was not exclusively connected to the Norse in later times, but which may have also been connected to peoples like the Wends. There are also notable similarities between this Bronze Age culture and the cultures we describe as Scythian to the east.

Southern Scandinavia in particular is also abundant in Bronze Age rock paintings, which show more easily identifiable imagery, as well as forms of symbolic language. The Bronze Age ancestors of Viking longships are also depicted in these rock paintings, and one can even see how the heads of these Bronze Age longboats also resemble the heads of serpents and waterhorses, just as the Viking dragon ships later possessed. Sometimes the ships themselves resemble worms or serpents more than they do boats, and, at least in my own interpretations, there is a reason for this. Sometimes this Bronze Age symbolism also depicts giant, horned gods or beings among smaller sized ordinary people. This is a subject I have gone into detail elsewhere, and which arguably connects to the ”stallo” in Sámi traditions. The Bronze Age paintings also show symbols that may be the “footprints” of these giant gods, as well as symbols that appear to represent the sun or more angelic celestial phenomena.

Photo below: a part of the Bronze Age symbolic paintings located at Hällristningar på Hästhallen, also known as Horsahallen in local dialect, similarly to how Scanian bækkahors is equivalent to Swedish ”bäckahäst” as shown earlier in this article, even if the general Swedish word is ”näck” (both ”bækkahors” and ”bäckahäst” mean ”beck/stream horse” in English. ”Hors” is a local word for ”horse” and is cognate to English ”horse”.This location is not located to far from Björketorp. The red arrows on the image below point to giant figures, one with claw-like hands and a large phallus. The blue arrows point to ordinary sized people. The green arrow points to a possible symbol implying a footprint of one of the gods. The violet arrow points to a more worm-like ship depiction. The black arrows point to dragon, horned-worm, horse-like heads on the front of the ships.

The last language I would like to mention here is Gutnish, arguably a language of Southern Sweden, but spoken on the island of Gotland and the smaller island of Fårö to the east of Öland in the Baltic Sea. There is also an archaic written language known as “Old Gutnish”, which is generally accepted to be a separate dialect of Old Norse, or a separate Old Norse language. The Gutnish everyday Gutnish language is also, like Scanian and Bondska for example, a language in its own right, and not a dialect of Swedish. Gotland was terribly important in historical times, and seems to represent a cultural crossroads, where Wendish, and more typically Pontic-Steppe cultural and linguistic features occur. The skeletons of medieval women were also found on this island, their heads elongated through artificial cranial deformation, something associated with the Huns and certain ancient Black Sea cultures, and also with for example certain Peruvian cultures, but not found elsewhere in the Nordic World. Gutnish is also distinct from Gotlandic, the dialect of Swedish spoken on Gotland, influenced by Gutnish, and should also not be confused with the Götamål language in Southern Sweden, nor with the Gothic Language, although the names of all of these are likely related. I have discussed elsewhere some aspects of how Gutnish, Gothic, Baltic and Slavic languages have crossovers.

Gutnish is known for its diphthongs, for example Gutnish äus or häus, Swedish hus, English ”house”, Gutnish stain, Swedish sten, English ”stone”, Gutnish snåi, Swedish snö, English ”snow”. There are also other differences in vowels, e.g. Gutnish bat, Swedish båt, English ”boat”. An example of a comparison which can be made with Slavic, which I have discussed differently elsewhere, is that to say ”you are” (singular), “thou art”, you would say däu jäst in Gutnish, compare Swedish du är, Scanian deu ä, Pite Bondska dö jär etc. The jäst form is similar to Slavic forms, e.g. Polish ty jesteś – “thou art”, Kashubian të jes – “thou art”. These connections may connect to a historic Slavic speaking people known as the Wends, who were as fiersome and expert sailors as the Vikings were. As I have discussed elsewhere - the Wends are associated with having built large wooden bulwarks upon water, one of which is known to have existed on a lake on Gotland.

I hope that this article was an interesting read. It is dedicated to my family, loved ones and to the ancestors of Scania and Southern Scandinavia.